Why Anasazi Works

Don’t Fix Them; Let the Goodness Come Out

By C. Terry Warner, Chairman of The Arbinger Institute

Shannon, 16, called her mother asking for help. This was her fourth arrest in four months for public intoxication. Given a choice between jail and entering the Anasazi outdoor survival program, Shannon chose Anasazi. She emerged from the trail 56 days later, physically, mentally, and spiritually a healthier person. When her mother and stepfather joined her for the last two days on the trail, there were hugs, tears, apologies, and expressions of gratitude. Shannon’s heart had changed. Why does the Anasazi experience “work”? What I tell you about it I have discovered first-hand. Because of my professional interest in people’s emotional problems and the interventions that claim to correct them, Anasazi’s founders, Larry Olsen and Ezekiel Sanchez invited me in 1989 to evaluate what they were doing. My family and I went out on the trail in the wilderness of Arizona. I talked with the students, watched their interactions, listened to inter-changes between students, instructors, and “shadows” (counselors), and interviewed parents. Subsequently, I have returned six or eight times and have come to know the Anasazi operation and have tracked the progress of quite a few students. The students’ progress continually amazes me. It far exceeds that of troubled youth in any of the other rehabilitative programs I have been able to learn about, including counseling, therapy, and psychiatry in both residential and outpatient settings.

Underpinning everything the Anasazi people do seems to be the unspoken assumption – the absolutely startling assumption – that the students do not need to be “fixed” or “straightened out.” Indeed, trying to get them to change, which requires trying to exercise some sort of control over them, only makes matters worse. On the other hand, caring about them and treating them with respect gives them the best opportunity for change on their own initiative. Like everyone else, teenagers want to do the responsible, mature thing when they can do it freely, but they can never be coerced or intimidated into doing it.

Influence without Manipulation

For this reason, students receive instruction only when they ask for it, including instruction in the ancient Indian survival skills. When they engage in the offensive and manipulative behavior that brought them to Anasazi, they expect their leaders to overreact, just as others in their lives have done. Though I have watched them carefully, I have not seen the Anasazi personnel overreact. They neither cave into childish demands nor act punitively. They respond cheerfully, empathetically, and respectfully – which means they continue to give the students the right to be responsible for themselves.

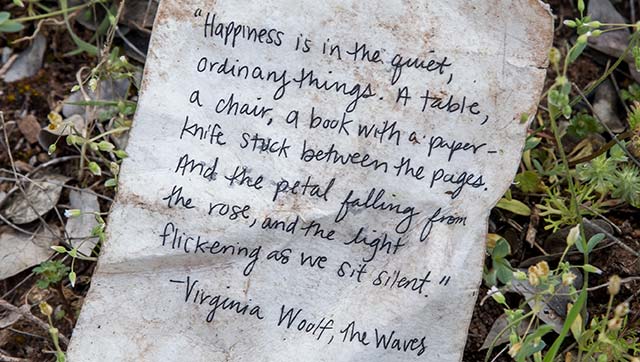

Nature helps significantly, for it doesn’t overreact either. The manipulative games by which students previously kept their world in perpetual disequilibrium do not work in the wilderness. The students must rely on honest effort in order to get on. Like the survival skills they learn on the trail, this builds their confidence in their ability to take care of themselves in tough circumstances. In the vast silence of the desert, they have time to reflect, to reconsider family relations, and to reassess their aims in life. They begin to discover who they really are and to like the person they find.

Family Complicity

Let me suggest why this kind of approach works so well. To do that, I need briefly to explore the dynamics of families whose children are troubled. Childrens’ problems are interconnected with the problems of other family members; they can maintain behavioral changes only to the degree that their parents make the same sort of changes. In exploring these delicate issues, I am pointing no fingers; just about all parents, including myself, have had the kinds of problems I will describe.

When we are sufficiently frustrated with a child to send him or her to “experts” to be “fixed,” we are not likely to share the Anasazi conviction that the child is a good person. “Obviously my child isn’t all right!” a parent may object. “She (or he) is rebellious, angry, defiant, calloused, promiscuous. She (or he) cares nothing at all about the values our family stands for, and keeps the family in constant turmoil. We have done everything in our power to bring about a change, including punishments and bribes, but nothing works. It’s pure folly to thing she (or he) will suddenly change just because we are loving and respectful. We’ve tried all that. Rest assured it would never work with this one.”

When we have this sort of attitude toward our children, they feel accused and blamed, and they resent it. That resentment leads them to act vindictively, to treat us and others in a calloused way, and to undermine our hopes for them. We in our turn feel unappreciated and mistreated, after all we have done for our children. Over time, this cycle of blame and resistance intensifies. Thus, “troubled” children typically come from troubled families – families in which the reciprocal blaming has become a way of life.

It is this way that children by their bad behavior both reflect their family’s attitude toward them and provoke more of that attitude. Having learned to worry about defending self, all of the family members, including the children, see the world defensively; they refuse to allow themselves to feel and be touched by the needs of others. And, they carry into other relationships – with teachers, counselors, police, friends, coaches – the skills of blaming, manipulation, and control developed in their families: they show off, act up, throw tantrums, get into fights, abuse drugs, become promiscuous. They get labeled as troubled, rebellious, defiant, incorrigible – as being somehow defective. And then – and here the cycle is completed – we as parents find it difficult to believe our children are basically good: we have made a habit of misinterpreting the bad behavior we have taught our children, calling it a sign of an intrinsically bad character.

You can see that in spite of the way we experience our children when we are caught up with them in this “death spiral,” they are simply responding to the way we are treating them. This means that when we think we see a negative personality trait in them, we are in error. A negative trait is not a characteristic of an individual, like height or red hair or musical talent. Instead, and in spite of appearances to the contrary, it is something the individual is doing in conjunction with other people.

For example: Suppose I see my child arguing with just about every request I make. “I don’t have time.” “It’s not my turn.” “Why don’t you ever ask Rodney to do the dirty work?” “You won’t let me go because you don’t trust me.” So I say in my heart, “This child is obstinate, defiant, and even cruel” – as if I were speaking of his or her nature. But the truth is that what this child is doing – the obstinance, defiance and cruelty – is only a response to me.

I can look at my own behavior and see that the way I am acting toward my child – demanding, mistrustingly, authoritatively, is contributing to my child’s response. The child and I are working together – collaborating – to produce that part of the child’s behavior that I find frustrating, and that part of my behavior that my child finds frustrating! The negative trait that I mistakenly think of a characteristic of the child is actually what the child and I are doing together!

One mother was convinced that her husband had abetted their daughter’s problems by failing to “lay down the law” forcefully enough. “We have allowed her to speak to us this way! She’s a foul-mouthed, disrespectful girl and we’ve let her get away with it!” In her mind, the problem was in her daughter, and the solution lay in controlling the daughter more effectively – “making” her be respectful, responsible, disciplined.

The mother communicated her feelings about her daughter by words, expressions and “body language.” “Our troubles are all your fault,” was the message that came across to her daughter. “You are unacceptable. You need to change.” In the face of such criticism, the daughter did not say in her heart, “Oh thank you, Mom, for pointing out all my faults to me. I’ll get started correcting them right away!” On the contrary, she responded in kind, accusingly and defensively, by thinking and sometimes by saying, “Who do you think you are? You’ve got no right to say I’m the one to blame. You’re the one who’s causing the problems!” Instead of changing in accordance with criticism, the daughter has every reason not to change, but instead to defend her behavior, continue in it, and blame her mother for blaming her!

Let me suggest why this kind of approach works so well. To do that, I need briefly to explore the dynamics of families whose children are troubled. Childrens’ problems are interconnected with the problems of other family members; they can maintain behavioral changes only to the degree that their parents make the same sort of changes. In exploring these delicate issues, I am pointing no fingers; just about all parents, including myself, have had the kinds of problems I will describe.

When we are sufficiently frustrated with a child to send him or her to “experts” to be “fixed,” we are not likely to share the Anasazi conviction that the child is a good person. “Obviously my child isn’t all right!” a parent may object. “She (or he) is rebellious, angry, defiant, calloused, promiscuous. She (or he) cares nothing at all about the values our family stands for, and keeps the family in constant turmoil. We have done everything in our power to bring about a change, including punishments and bribes, but nothing works. It’s pure folly to thing she (or he) will suddenly change just because we are loving and respectful. We’ve tried all that. Rest assured it would never work with this one.”

When we have this sort of attitude toward our children, they feel accused and blamed, and they resent it. That resentment leads them to act vindictively, to treat us and others in a calloused way, and to undermine our hopes for them. We in our turn feel unappreciated and mistreated, after all we have done for our children. Over time, this cycle of blame and resistance intensifies. Thus, “troubled” children typically come from troubled families – families in which the reciprocal blaming has become a way of life.

It is this way that children by their bad behavior both reflect their family’s attitude toward them and provoke more of that attitude. Having learned to worry about defending self, all of the family members, including the children, see the world defensively; they refuse to allow themselves to feel and be touched by the needs of others. And, they carry into other relationships – with teachers, counselors, police, friends, coaches – the skills of blaming, manipulation, and control developed in their families: they show off, act up, throw tantrums, get into fights, abuse drugs, become promiscuous. They get labeled as troubled, rebellious, defiant, incorrigible – as being somehow defective. And then – and here the cycle is completed – we as parents find it difficult to believe our children are basically good: we have made a habit of misinterpreting the bad behavior we have taught our children, calling it a sign of an intrinsically bad character.

You can see that in spite of the way we experience our children when we are caught up with them in this “death spiral,” they are simply responding to the way we are treating them. This means that when we think we see a negative personality trait in them, we are in error. A negative trait is not a characteristic of an individual, like height or red hair or musical talent. Instead, and in spite of appearances to the contrary, it is something the individual is doing in conjunction with other people.

For example: Suppose I see my child arguing with just about every request I make. “I don’t have time.” “It’s not my turn.” “Why don’t you ever ask Rodney to do the dirty work?” “You won’t let me go because you don’t trust me.” So I say in my heart, “This child is obstinate, defiant, and even cruel” – as if I were speaking of his or her nature. But the truth is that what this child is doing – the obstinance, defiance and cruelty – is only a response to me.

I can look at my own behavior and see that the way I am acting toward my child – demanding, mistrustingly, authoritatively, is contributing to my child’s response. The child and I are working together – collaborating – to produce that part of the child’s behavior that I find frustrating, and that part of my behavior that my child finds frustrating! The negative trait that I mistakenly think of a characteristic of the child is actually what the child and I are doing together!

One mother was convinced that her husband had abetted their daughter’s problems by failing to “lay down the law” forcefully enough. “We have allowed her to speak to us this way! She’s a foul-mouthed, disrespectful girl and we’ve let her get away with it!” In her mind, the problem was in her daughter, and the solution lay in controlling the daughter more effectively – “making” her be respectful, responsible, disciplined.

The mother communicated her feelings about her daughter by words, expressions and “body language.” “Our troubles are all your fault,” was the message that came across to her daughter. “You are unacceptable. You need to change.” In the face of such criticism, the daughter did not say in her heart, “Oh thank you, Mom, for pointing out all my faults to me. I’ll get started correcting them right away!” On the contrary, she responded in kind, accusingly and defensively, by thinking and sometimes by saying, “Who do you think you are? You’ve got no right to say I’m the one to blame. You’re the one who’s causing the problems!” Instead of changing in accordance with criticism, the daughter has every reason not to change, but instead to defend her behavior, continue in it, and blame her mother for blaming her!

Those bullying parents you occasionally see in the supermarket or on the little league playing field, loudly chastising a terrorized child for a minor offense, are not the only ones who provoke their children to defensiveness and defiance. Perfectly “proper” parents do too. Larry Olsen says the preponderance of Anasazi students come from “respectable” homes where one parent or both insist on always doing things the “right” way, by scolding or otherwise emotionally punishing the child who falls short, in the misguided conviction that this will push the child to get back on track.

Such parents insist they are standing up for what’s right and that the child won’t cooperate; they can’t be blamed for this child’s waywardness. But this controlling style of parenting is just what provokes the child’s bad behavior. They mistakenly think the “correctness” of their parenting program (“for the child’s own good”) somehow justifies the rejecting attitude they carry in their hearts. Their demands that “right” be done feed wrong-doing.

What must be understood about child-rearing is that when children resist their parents’ control tactics by refusing to clean up their room, by hanging out with rebels, by sleeping around, or by doing drugs, it is not because they find these things intrinsically appealing or because they are intrinsically “bad” children. In spite of appearances to the contrary, these things do not really matter to them. What matters to them is the protection of their agency, independence, and identity, which they feel are being threatened. Like the rest of us, children fight for the God-given right to think and act for themselves.

Thus the issue over which family members wage their power struggles is never the real issue for the child. The real issue is whether the parent is going to recognize the child as a real person and respect his or her agency – and this means loving the child without reservation, never punishingly more indulgently, but with high expectations. It means that the parents must let go of their own insecure quest to maintain control.

Those bullying parents you occasionally see in the supermarket or on the little league playing field, loudly chastising a terrorized child for a minor offense, are not the only ones who provoke their children to defensiveness and defiance. Perfectly “proper” parents do too. Larry Olsen says the preponderance of Anasazi students come from “respectable” homes where one parent or both insist on always doing things the “right” way, by scolding or otherwise emotionally punishing the child who falls short, in the misguided conviction that this will push the child to get back on track.

Such parents insist they are standing up for what’s right and that the child won’t cooperate; they can’t be blamed for this child’s waywardness. But this controlling style of parenting is just what provokes the child’s bad behavior. They mistakenly think the “correctness” of their parenting program (“for the child’s own good”) somehow justifies the rejecting attitude they carry in their hearts. Their demands that “right” be done feed wrong-doing.

What must be understood about child-rearing is that when children resist their parents’ control tactics by refusing to clean up their room, by hanging out with rebels, by sleeping around, or by doing drugs, it is not because they find these things intrinsically appealing or because they are intrinsically “bad” children. In spite of appearances to the contrary, these things do not really matter to them. What matters to them is the protection of their agency, independence, and identity, which they feel are being threatened. Like the rest of us, children fight for the God-given right to think and act for themselves.

Thus the issue over which family members wage their power struggles is never the real issue for the child. The real issue is whether the parent is going to recognize the child as a real person and respect his or her agency – and this means loving the child without reservation, never punishingly more indulgently, but with high expectations. It means that the parents must let go of their own insecure quest to maintain control. Character, Not Techniques

The manipulative games by which students previously kept their world in perpetual disequilibrium do not work in the wilderness. Why don’t the standard group methods – the cooperation games, trust exercises, rope courses, and other rehabilitative techniques—work as well as respecting the students’ agency? It’s because no matter how persuasive the theory behind these designed experiences, and no matter how favorably the students may respond to them, they share the very same assumption that led to the students’ trouble in the first place, namely, that the students are deficient (in skill, character or attitude) and need someone to take charge of them and change them. And who better to do the job than the so-called experts? But what many experts don’t comprehend is this: When the methods by which we try to change people represent more efforts to control them, these methods ultimately give them more reason to resist. It is because we seek to take responsibility for them that they don’t take responsibility for themselves.

Control will sometimes coerce compliance from the child, but it will never win allegiance and commitment to the parents’ professed values, and never foster the child’s growth in personal responsibility. And the more parents engage with their children in the power struggles that controlling parenthood initiates, the more they collaborate in the children’s passively compliant, demoralized, or defiant behavior. Too often, professionals’ rehabilitative techniques are used for controlling purposes that at the bottom are not very different from those a dysfunctional family uses.

The ugliest illustration of this I have ever heard was perpetrated upon a former ANASAZI student. Refusing to accept their share of responsibility for her problems, her parents blamed her when tension arose again in the family, and they enrolled her in another youth rehabilitation program. This one required the parents to write down and report everything she said and did; then the rehabilitative staff confronted her with the evidence that she was the problem.

Later, hoping she was making progress, Olsen visited her and discovered a 15-year old who was intimidated, broken in spirit, and without vitality. She told him she was not doing wrong anymore, but had lost her desire for life and longed to return to the trail, where she had done well out of desire and not out of fear.

Power, control, psychological manipulation – these backfire. What “works” is love. The crucial difference between those professionals who help the child and those who don’t is a matter of character, not of method.

The manipulative games by which students previously kept their world in perpetual disequilibrium do not work in the wilderness. Why don’t the standard group methods – the cooperation games, trust exercises, rope courses, and other rehabilitative techniques—work as well as respecting the students’ agency? It’s because no matter how persuasive the theory behind these designed experiences, and no matter how favorably the students may respond to them, they share the very same assumption that led to the students’ trouble in the first place, namely, that the students are deficient (in skill, character or attitude) and need someone to take charge of them and change them. And who better to do the job than the so-called experts? But what many experts don’t comprehend is this: When the methods by which we try to change people represent more efforts to control them, these methods ultimately give them more reason to resist. It is because we seek to take responsibility for them that they don’t take responsibility for themselves.

Control will sometimes coerce compliance from the child, but it will never win allegiance and commitment to the parents’ professed values, and never foster the child’s growth in personal responsibility. And the more parents engage with their children in the power struggles that controlling parenthood initiates, the more they collaborate in the children’s passively compliant, demoralized, or defiant behavior. Too often, professionals’ rehabilitative techniques are used for controlling purposes that at the bottom are not very different from those a dysfunctional family uses.

The ugliest illustration of this I have ever heard was perpetrated upon a former ANASAZI student. Refusing to accept their share of responsibility for her problems, her parents blamed her when tension arose again in the family, and they enrolled her in another youth rehabilitation program. This one required the parents to write down and report everything she said and did; then the rehabilitative staff confronted her with the evidence that she was the problem.

Later, hoping she was making progress, Olsen visited her and discovered a 15-year old who was intimidated, broken in spirit, and without vitality. She told him she was not doing wrong anymore, but had lost her desire for life and longed to return to the trail, where she had done well out of desire and not out of fear.

Power, control, psychological manipulation – these backfire. What “works” is love. The crucial difference between those professionals who help the child and those who don’t is a matter of character, not of method.